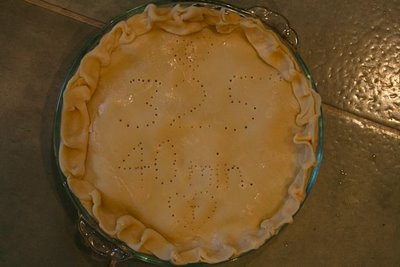

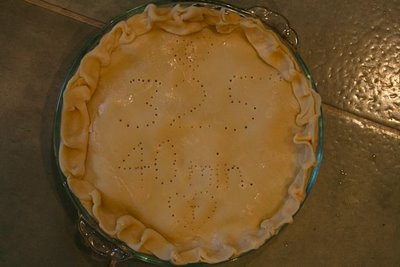

We might as well start with the chicken pot pie. In my packing frenzy as I prepared for ten days in Guyana, South America, I also went into a cooking frenzy. Realizing that baking is not one of Bill of the Birds' myriad fortes, I left instructions on the fully assembled but uncooked pie. Sure enough, he called me at the airport to ask me how long he should bake it. "Just take the pie out of the fridge and look at it!"

There followed a series of long flights, a 10:30 PM arrival at the one-gate Georgetown airport, an 11:30 PM arrival at the Grand Coastal Hotel an hour away, and a comatose night. At 5:30 the next morning, we left for our first outing, a pattern that would continue for the entire ten-day trip: rising in the dark to constant motion until it was time to collapse back into bed. Our destination was a marshy savannah within earshot of Guyana's coast. Here, birds like laughing falcons, named for their ha-ha-hoo-hoo call, stand sentinel on palm trunks.

before flying off.

There's nothing like a laughing falcon anywhere in the States, but we do have snail kites--an endangered species, found only in the Florida Everglades. In Guyana, they sit all over the powerlines, diving down occasionally to nab an apple snail from a roadside ditch. It's nice to see them being all abundant. This is an immature snail kite.

We'll see it use its specialized hooked bill in a future post.

We had a couple of target birds for this outing, found only in Guyana. One was the blood-colored woodpecker, a small bird which cleverly eluded us for the entire trip, showing only bits of itself before winging away, as if headed for Venezuela. I managed to photograph the back and wings of an immature female. I'm told the male is a real stunner. Still, you can see some red on her back.

All told, this is typical of my Guyanan bird photos. Now, I got some dandies, but the vast majority of the 2000 exposures I made were garbage. This was without doubt the most challenging environment for photography I've ever encountered: hot and humid as anyplace I've ever been, with a blinding bright sky and deep dark jungles, thick with tangled greenery. Most of the birds were right up against that blinding sky, smack dab in the middle of a vine tangle, or just under the canopy of the deep dark jungle against the bright bright sky. Suffice it to say I learned a lot about the limitations of a camera in these conditions.

Another Georgetown specialty: the white-bellied piculet, sort of like a miniature woodpecker, the size of a small nuthatch. Here's the female, preening. It's OK if you yawn. We were pretty excited, but then we're birders, and the word "endemic" (found nowhere else on the planet) gets our hearts pumping, no matter what the bird looks like.

The male dresses it up with a red forecrown, but he is careful to hide behind sticks.

Even those of us with huge lenses succumbed to the conditions, and even got all balled up in our gear from time to time. Here's Michael Weedon, Associate Editor for England's

Birdwatching Magazine, trying to figure out which strap goes to which so he can get his camera free. He toted the most gear of any of us, and thanks to that scope and a pocket camera, also got some of the best pictures, I daresay.

We moved on from the white-bellied piculet to something more powerful: a crimson-crested woodpecker, member of the exalted genus

Campephilus, and thus a cousin to our much sought-after ivory-billed woodpecker. Just a peek, but the stance is soooo familiar:

Oh, please come out. I need to see you.

Oooh! Look at your beautiful head!

Thank you.

Everything about you, your huge semi-circular claws and your powerful bill, your erect carriage and your proud crest, haunts me, reminds me of what might yet be in our southern swamps.

Because there were lots of things like iguanas

and tegus (a life lizard for me!)

scurrying in the savannah forest, there were lots of things like this rufous crab hawk sitting around scanning for prey. This is a dandy huge gorgeous beast, perfectly lit and situated for his portrait, and, like the piculet, careful to have several branches in front of him for good composition.

OK, now, try to get me flying through the same branches. Good work.

His main dietary item appears as dots in this photo. Like the snail kite, he's surrounded by food all the time. Every dot in this picture is a fiddler crab. Yum!

The marshes in Guyana are themselves often dotted with the beautiful little pied water-tyrant, a member of the flycatcher family, which has speciated wildly in South America. There were two full pages of flycatchers in our Guyana checklist, and my eyes glazed over when trying to identify most of them. I prefer tyrants to many other flycatchers, because they are so unequivocally marked.

Female and immature pied water tyrants have some black on head, back and wings.

A good male will knock your socks off. I am not sure what the adaptive value of being so obvious might be. It is not obvious to me.

Our guide to all this beauty was Andy Narine, a Rastafarian birder of East Indian (to distinguish from West Indian) extraction.

He's one of the leaders in Guyanan birding, keen of eye and ear and encyclopedic of knowledge. His lilting Caribbean accent lapsed freely into musical Creole, gorgeous and sometimes hilarious to hear. We were definitely not in Kansas any more.

Showing us birds all the way, Andy led us along the coast, where an unexpected dot of scarlet resolved into my life scarlet ibis. I cannot tell you how exciting it was to have a flourescent red bird appear out of nowhere. I was jabbering and hooting and hollering. Pure, vibrant color does that to me, and life birds do that to me, but give me a life bird that is a pure, vibrant color and Sally bar the door.

Again, adaptive value of this flaming color: unknown. Just beautiful, that's all.

Terry Moore of Leica was kind enough to dial Bill on his cell phone and hand it to me so I could stutter, "Scarlet ibis!!" to my surprised mate. It would be the last time we'd speak for ten days.

Too soon, it was time to drop Andy off at his office, where he heads a natural history society. Thanks so much, Andy Narine. You are awesome and 'ital, mon.

Labels: Andy Narine, blood-colored woodpecker, crimson-crested woodpecker, Georgetown, Guyana birding, iguana, laughing falcon, rufous crab hawk, tegu, white-bellied piculet

Of course, you bring the dog, because otherwise he'll try to run along the shore, or howl, or both.

Of course, you bring the dog, because otherwise he'll try to run along the shore, or howl, or both.  Besides, he knows the way.

Besides, he knows the way.

But then protein is where you find it, and even in our distress, most of us have no idea what it is to live so close to the bone. I didn't see many overweight people in Guyana.

But then protein is where you find it, and even in our distress, most of us have no idea what it is to live so close to the bone. I didn't see many overweight people in Guyana.