Ixpanpajul

On Birdwatching Encounters in Guatemala, we see a lot of different places. Sometimes the travel time to get there unavoidably eats up the time we'd LOVE to be spending in birdwatching. Such was the case at Parque Nacional de Ixpanpajul, a historic Mayan site that boasts tramways and suspension bridges from which one can watch birds and other jungle life. We got there just at nightfall, and hurried down a shadowy trail to see what we could see before dinner. Warning: my photos are about as good as you'd expect for pictures taken, handheld, at 1600 ISO at nightfall. They suhhhhhk.

Right before the light died I got this picture of begonias growing along the trail, huge begonias, unknown and deathly exciting to a houseplant maven.

A little oncidium orchid, fallen from high above, bloomed bravely on the forest floor.

A little oncidium orchid, fallen from high above, bloomed bravely on the forest floor.

Our guide was amazing. Not a word of English, but he saw every pajarito there was to see, way before we did, and he could whistle through a rolled tongue just like a tinamou or a laughing falcon. I was humbled by his presence, honored to be in his company. He was a woodsman, a rare one. One such pajarito was a red-capped manakin, and I was privileged to be standing beside Mike Bergin (of 10,000 Birds reknown) as he ticked that one off on his life list. If you ever get a chance to go birding with Mike, grab it! Bill and I are already trying to figure out how to enjoy his witty, warm and bright company again soon. He's a live one.

Pity this manakin does not know how famous he is, being Mike Bergin's First Manakin and all. Manakins seem like the kind of birds that would enjoy being notorious.

Pity this manakin does not know how famous he is, being Mike Bergin's First Manakin and all. Manakins seem like the kind of birds that would enjoy being notorious.The unidentified fluffy mass on the tree in this pathetic picture proved to be the nest of a lesser swallow-tailed swift, constructed of plant down and swift saliva. It had a tubular entrance pointing straight down.

This is what's nice about having people like Steve Howell, author of Birds of Mexico, on one's trip! We'd never have known what it was otherwise. He's also a very fun guy. I wish I had had a chance to go birding with him, but life intervened.

This is what's nice about having people like Steve Howell, author of Birds of Mexico, on one's trip! We'd never have known what it was otherwise. He's also a very fun guy. I wish I had had a chance to go birding with him, but life intervened.An ivory-billed woodcreeper searched for insects. I love the fine pearls running over his shoulder and mantle.

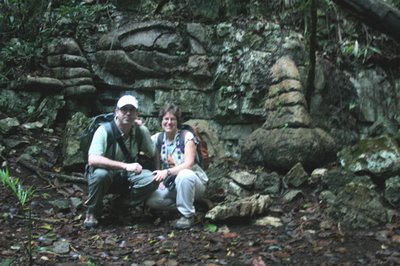

The best was yet to come. Our guide hurried to get us to an archaeological site before it was completely dark. Scrambling up slick stone stairs, we were felled by the vision of a huge eye and nose emerging from jungle vegetation. Wow, wow, wow.

Tikal is cool, but it has nothing to compare to this for sheer grab-you-by-the-psyche impact.

photo by Jim McCormac

A lot went on in these jungles that we know almost nothing about. I'm currently reading 1491

by Charles C. Mann. It's about what native societies might have been up to before Columbus "discovered America." The author ranges from Massachusetts all the way to Guatemala and Bolivia, examining evidence that the "New World" was much older, better developed and much more densely populated than we have heretofore believed. It's fascinating, but dense, and I find my eyes swimming and head nodding each night as I try to wrap my mind around the concept.

Just looking into the Maya guide's eyes, getting a nonverbal dose of the volumes he knew about birds, was a lesson in humility. We prance around with our books and optics, but he knows. I'm sorry not to have a picture of him, but sometimes I feel awkward acting touristy around someone so learned. His ancestors built that face, now smothered in jungle.

Labels: 1491, ivory-billed woodcreeper, Ixpanpajul Guatemala, lesser swallow-tailed swift nest, Mayan sculpture, red-capped manakin